The Kindest Garden – How are Ecosystems the Network of Life?

Economy without ecology means

managing the human nature relationship

without knowing the delicate balance

between humankind and the natural world

Satish Kumar

The word ecosystem comes from the Greek oikos, meaning household. A system is an interconnecting network that works as a whole. Jainian monk and environmentalist Satish Kumar once explained to an audience of economists (from the Greek oikonomia, ‘household management’) that their real job was the management of the whole household of the natural world, not only money – otherwise they would just be money-managers. If we do not look after the biological eco-home then there will be no money, nor people to manage it for.

CREATING A HAVEN: A PRACTICAL GUIDE TO PLANNING AN ECOSYSTEM GARDEN

There can be no purpose more enspiriting than to begin the

age of restoration, reweaving the wondrous diversity of life

that still surrounds us.

E.O. Wilson

You may have been taught ‘right plant right place’ in terms of sun, shade and soil type. Once we also begin working with where plants choose to grow, and which other plants they associate with, we open up a whole new dimension to creating a garden that functions and feels deeply comfortable, as a near archetype that we recognise at an atavistic level. The next layer then is to cater for the many animals that associate with different plants and set the stage for a garden full of abundance and life.

Observe the insects and birds that visit areas of planting to build up a picture of the nectar and forage hotspots in your garden at any given time. They will move around the garden during the day and over the months as areas become sunnier and warmer, and plants blossom and fade. For each season plan a spread of plant shapes that are most attractive to the foragers currently in search of food. Include generalists and specialists, varying the plant shapes through the garden rather than providing a homogenous covering.

Plan for about 60 per cent generalists – magnets for lots of different insects. These are the ‘party plants’, like marjoram (Origanum majorana), knapweed (Centaurea nigra) and many of the umbellifers and Asteraceae, where nectar is on tap and everyone is invited. Often white or yellow, the umbellifers may have an evolutionary advantage with light wavelengths that most insects can see. The Asteraceae’s appeal is in its inflorescence: being made of lots of little flowers with short corollas, these give easy access to the nectaries. Both umbellifers and Asteraceae will be covered in bees, butterflies, hoverflies, flies, sawflies, beetles and butterflies throughout the flowering season. Although having plenty of generalists means you will attract many pollinators, these may need many visits to ensure cross pollination. Of all insects, bumblebees, followed by solitary bees, are the most prolific pollinators.

Your planting should also ensure forage for specialists, including night-scented flowers for moths. Specialist flowers are particularly attractive to a few bee species: for example, bellflower (Campanula) offers food to bellflower blunthorn bees and small scissor bees; yellow loosestrife (Lysimachia vulgaris) supports yellow loosestrife bees, which collect the pollen and also the oils to waterproof their nest cells.

Plants with tubular flowers like winter-flowering honeysuckle (Lonicera fragrantissima) or later-flowering trumpet vine (Campsis radicans) are a draw to long-tongued bees and moths, which can reach down into the corolla, as well as to some ‘robber’ bees, which will pierce the corolla at the top to reach the nectar. Legume pollen is a rich source of protein for pollinator larvae, so plan a mix of Fabiaceae to suit different tongue lengths of foragers and so benefit insects and nearby farmers. Summer-flowering crimson clover (Trifolium incarnatum) will support long-, mediumand short-tongued bumblebees as well as some hoverflies, while red clover (T. pratense) feeds long- and medium-tongued hoverflies.

Trees, shrubs and climbers are also important. Listen to the buzz of mature ivy (Hedera) in flower in late summer – a nirvana to ivy bees, while early-flowering willows (Salix caprea and S. alba) are mobbed by hungry bees emerging from hibernation in spring. The purpose of pollination is to set fruit, seed and reproduce. Flowering at different times of year helps, both by allowing enough time to ripen fruit and disperse seed, and by flowering when the right pollinators are available. The bee orchid tempts the male bee to land on its female-bee-mimicking pad by emitting pheromones, but gives no nectar. This strategy wouldn’t work for long, but the bee orchid flowers when the young males are just starting to fly, so benefits from their naivety. Not all plants need pollination, however: some beans and peas are self-fertile, and grasses like wheat and oats are wind-pollinated. Some fruits and vegetables are self-pollinated but benefit from additional ‘buzz’ pollination to produce edible fruits. Tomatoes and aubergines hold their pollen in hollow anthers that are ‘shaken’ by bees’ high-frequency wing vibrations to rain on to the flowers below. It is not understood why bees buzz exactly when they do, but we do know that bumblebees and solitary bees do this, so position bee-attracting companion plants like garden catmint (Nepeta Å~ faassenii) by an open greenhouse.

Build a variety of bee nesting sites through the garden to suit these visitors. These can range from the hollow stems in cow parsley (Anthriscus sylvestris) to dead bark for beetles. Erect a vertical compost bay to allow overwintering insects to stay in hollow stems and emerge in spring rather than succumb to rot in a compost heat or be chipped or burnt on a bonfire. Leafcutter bees like to make nests in old fences, plant stems and dead wood and line their cells with pieces of leaf from roses and wisteria glued together with saliva. Bee hotels are useful in gardens without these homes, in which case tubes should vary in diameter and be 20cm (8in) deep to allow for the female larvae to be encased deep inside. Shorter lengths may result in only males.

Detritivores are key to any circular system and your compost heap and woodpile will provide good habitat, as will leaving wood on the ground and dead bark for beetles. Make sure to include water. As the dragonfly food web example showed, water is vital to an ecosystem as an algal food source as well as for the amphibians it will support, whether the water is in a lake, a rill or a bathtub pond. Don’t rush to put fish in a small pond, though; they can be overzealous predators on both plants and frog and newt tadpoles and can raise nutrient levels beyond those that can be recycled.

A thriving garden ecosystem will also include mammals, from field mice and shrews to increasingly rare harvest mice and hedgehogs, and to badgers and foxes. Find your own balance between tidiness and tolerance. Cover and connectivity are the key needs, so establish areas of scrub in larger spaces or woodpiles in smaller ones for habitat, plus longer grass and dead hedges contiguous with live hedgerows, for corridors between forage hotspots and homes.

I am often asked about the ‘problem’ of mice, and my answer is owls. Mice eat seeds, fruit and insect larvae as well as human leftovers and are in turn a food source for the tawny owl, barn owl, buzzard, fox and badger. In the greenhouse a mouse-proof winter seed tray is a great boost for human–mouse relations. If the mice are too hungry in the vegetable garden, peppermint oil helps to send them elsewhere.

Spiders are a vital part of the ecosystem, and I refer any fearful readers to the children’s book Charlotte’s Web. These extraordinary creatures help reduce flies and moths in our houses, and in the UK very few will bite and none is poisonous. I was once tempted to use a sonic mouse repellent, which emits a high-pitched noise to repel mice, in my 1490s house. I didn’t realise that it repelled spiders as well, until we noticed an influx of houseflies in droves. The plug-in kit was quickly recycled!

In nurturing ecosystems our aim is to increase resources, to put back into a syntropic system and help more life to thrive. On a large scale this might be reconnecting a floodplain to its river, by paying attention to the way the water flows and following the path of least resistance. This gentle morphology translates well to a garden setting, where we can observe, see what is needed and provide it. The simplest of these is adding shallow water scrapes or bowls for dry weather. See where birds and bees drink from puddles and ensure some water every 10– 30m (33–100ft) – the maximum distance a small mammal will run across an open space.

Reducing hedgerow cuts to every three years is a stipulation in higher-tier countryside stewardship on farmland, and a good idea in residential gardens too. This allows songbirds greater protection from predators and allows fruits to form, feeding hungry migratory birds like redstarts as well as providing humans with forageable hips to ward off winter flu.

If there is no chance of a hedgerow, a beetle bank is a great addition to a field or meadow. A simple bund, about 40cm (16in) high and 2m (7ft) wide, will give cover for small mammals and invertebrates and has been found to shelter birds too. It’s a simple structure to recreate in a vegetable garden or car park, to link with hedgerows and provide the vital connectivity for small mammals, as well as hunting grounds for larger mammals and birds of prey.

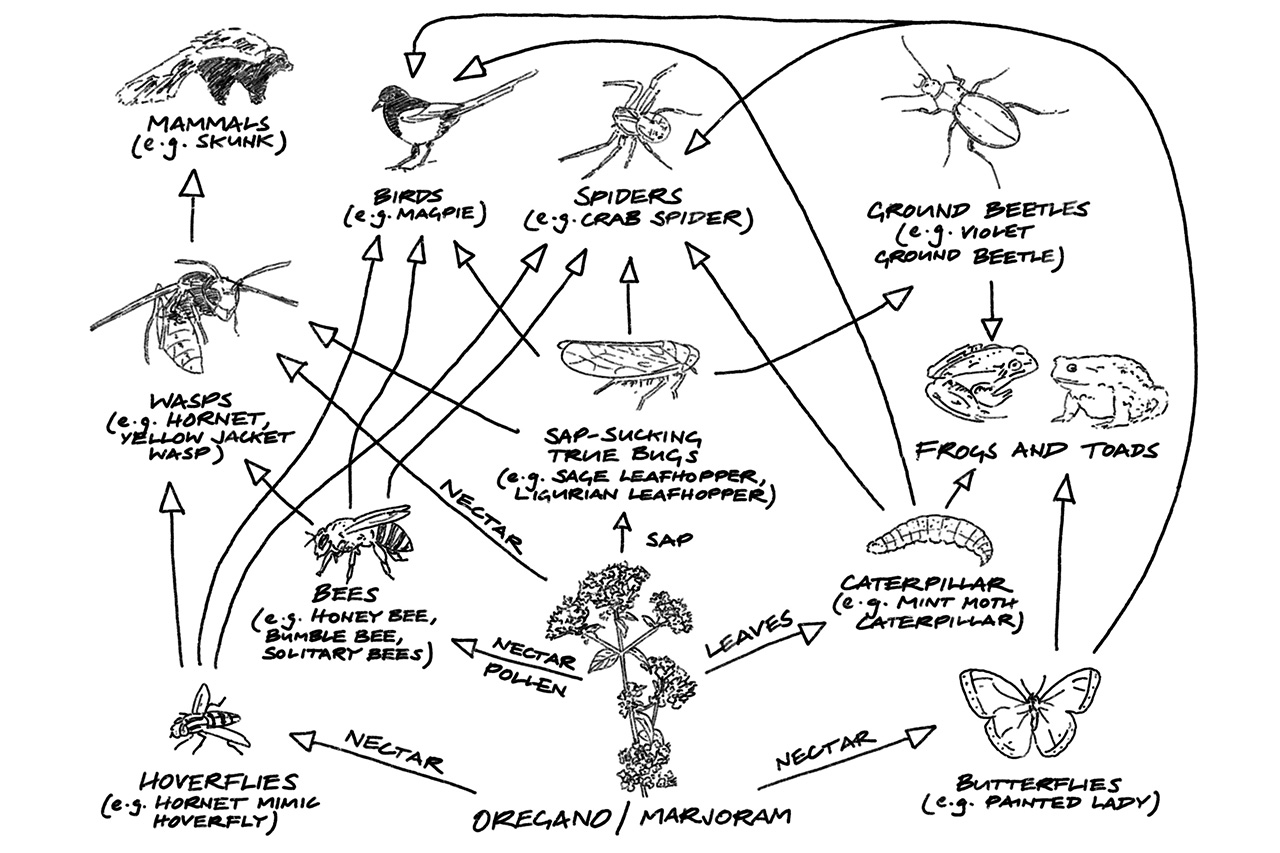

The Oregano Foodweb

HOW TO: CREATE HABITAT SAND BOXES AND LOG PILES

At the smallest scale a simple log pile or sand box is an excellent habitat for mining bees and solitary wasps. In the tiniest of spaces, a wine box will do! Simply drill a few holes to allow insects to burrow into the sides, fill with sand and position in a sunny spot. I added a couple of resilient plants – herb Robert (Geranium robertianum) and lemon balm (Melissa officinalis) to the sand box – but selfseeders will also find their way in.

If you have some logs a log pile will provide a home to detritivores and mining bees as it gradually decomposes over a long time. If you can put one in the shade and one in the sun you will find different species take advantage of them.

Constructing a sand box

You will need:

- Reclaimed timbers of random lengths and widths

- Old bricks, logs and any non-toxic building items

- Horticultural sand

1. Gather even lengths and matching random widths of the reclaimed timber, for three sides of about 45cm (18in) high and a lower front for the sand box. There is no need for a base.

2. Fill the bottom with the bricks, logs and any nontoxic building items. Top up with the sand.

3. Slope the sand from front to back to allow maximum south-facing slopes for warming insects.

4. Place the sand box in a sheltered, south-facing location.

Making a log pile

You will need:

- Logs of 40–50cm (16–20in)

- Electric drill and drill bit for 8–15mm holes

1. Pile up logs in descending size to keep the pile stable.

2. Drill straight holes, 20cm (8in) deep to ensure mining bees lay female eggs. (If any hole is too short, bees will only lay the male ‘guard’ eggs, which they consider more expendable.)

Photo © Jason Ingram. Diagrams © MBLA