The Kindest Garden – Materials: How to Choose Materials to Work With

Buy less, choose well, make it last.

Vivienne Westwood

The materials we use to build landscapes and structures in them shape our environment. From locally sourced, natural. stone to complex composites, there is a wealth of options for a variety of budgets, aesthetics and performance requirements. The wide range of products and eco claims can make the choice overwhelming, and polarities are too often drawn, suggesting that all concrete or all greenhouse gases are ‘bad’ (where would we be without carbon dioxide, oxygen and H2O?) and all timber is ‘good’, when in fact that depends on how it is grown, used and disposed of.

The best option is to use materials already on site, from recycled paving setts to salvaged concrete aggregate. When it is not feasible to use reclaimed, the next best alternative will depend on several factors besides aesthetics and financial cost: how far the material comes from and how it was manufactured (both in terms of materials and human impact), with some materials still relying on forced or child labour and unsafe work conditions. How easy is it to repair, deconstruct and reuse, and where will it or its components go at end of life? Will it decompose gradually into the land or emit methane in landfill, for example? Is a ‘natural’ product farmed in a biodiversity desert, grown as a monoculture and reliant on fertilisers and pesticides, which pollute watercourses and enter the food chain, or is it contributing to a balanced future in harmony with nature and limiting chemical usage?

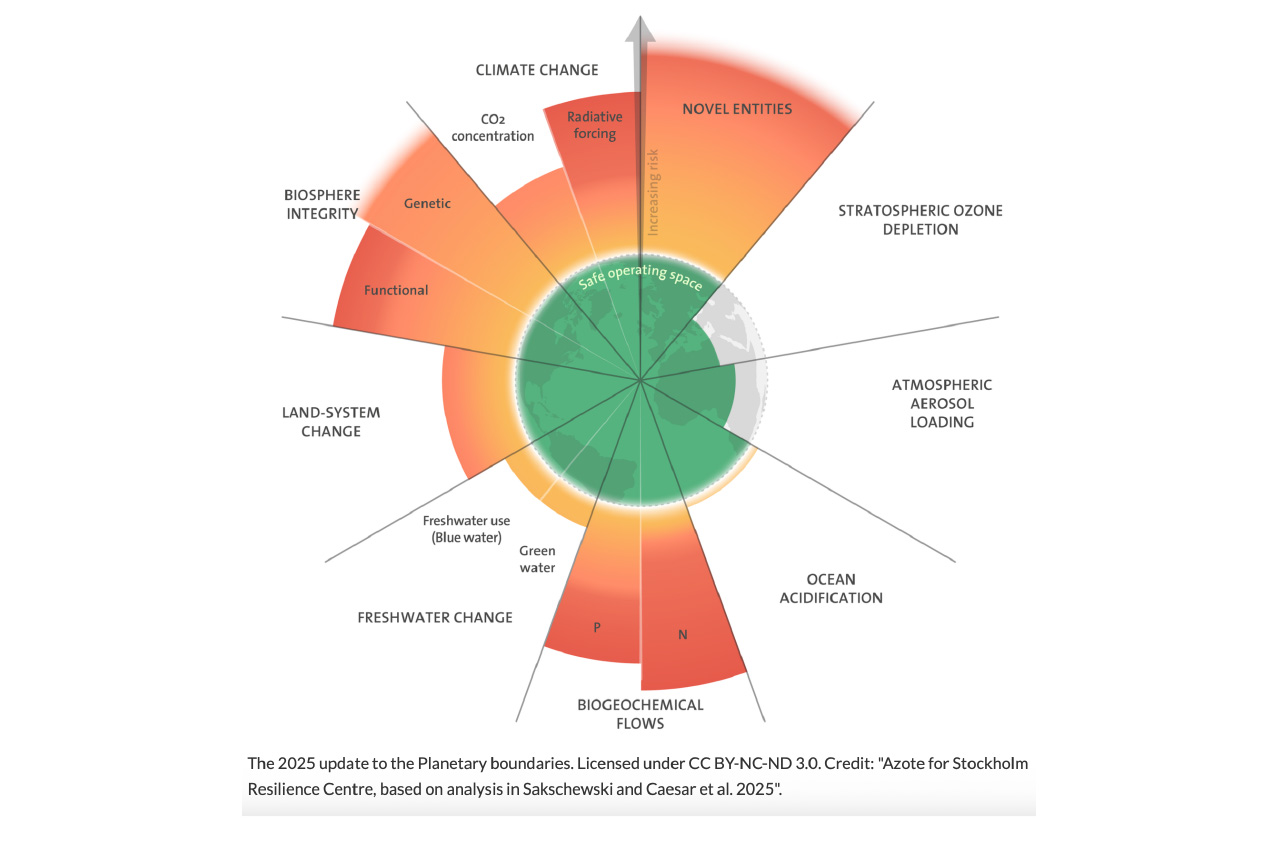

The Planetary Boundaries Framework was created in 2009 by Johan Rockström at the Stockholm Resilience Centre to describe and measure the nine major boundaries within which humanity can continue to thrive for generations to come. It is constantly updated and is a useful framework for decision-making, particularly when choosing materials.

Some key issues to look at include the following:

- Climate impact

- Fresh-water impact

- Biosphere integrity

- Stratospheric ozone depletion

- Atmospheric aerosol loading

- Acidification and eutrophication

Assessing all of these factors is complex, and information on the environmental impact of materials is still patchy. Some suppliers are very transparent, while others have very little publicly available data. In many cases it is necessary to make assumptions grounded in an understanding of the material and its use.

Environmental product declarations (EPDs), where available, are excellent sources of information. An EPD presents the results of a life-cycle assessment (LCA) of a material or product in a standardised format. A range of environmental impacts are reported, from carbon footprint to water use.

An LCA evaluates environmental impacts from raw material extraction to finished product, as well as looking at the ‘usage’ stage and end of life (removal and disposal). It often incorporates a measure of recycling or reuse potential: for example, the carbon emissions offset by reusing rather than re-manufacturing. EPDs are produced following the LCA methodology and are verified by an approved independent verifier before being published.

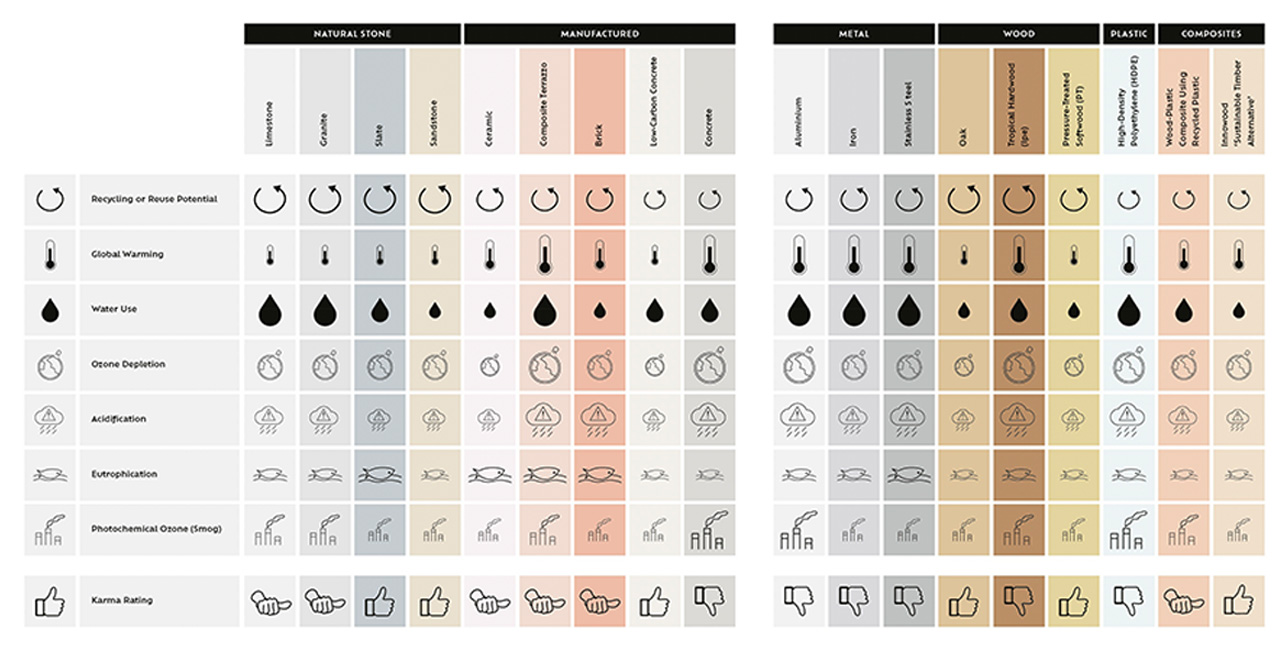

EPDs can seem overly technical to the nonprofessional, but it is worth downloading them and at least looking at sections A1 to A3, which show the impact of the raw material, transport supply and manufacture of each product and can be used to compare and choose between products. In the table overleaf we have analysed EPDs for some metal, wood, plastic and composite products and illustrated the EPDs in graphic form, adding our own subjective karma rating as a summary. This is a useful process, which I recommend to every design studio and significant user to create a decision-making tool. Some pieces of design software such as Vectorworks and Revit allow data sets to be linked to drawings and have growing databases of the carbon footprint of building materials to integrate in building information modelling (BIM). There are no easily integrated measures of sequestered carbon yet, however, but these will surely come.

In the table we have analysed EPDs for some metal, wood, plastic and composite products and illustrated the EPDs in graphic form, adding our own subjective karma rating as a summary.

UNDERSTANDING MATERIALS FOR GARDENS AND LANDSCAPES

We learn from our gardens to deal with the most urgent question of the time: how much is enough?

Wendell Berry

There are so many materials available – how best to choose? When selecting hard landscape materials, it pays to research the local geology through sites like bgs.ac.uk. Visit local quarries, managed woodlands and sawmills. Discover materials that have a relationship with your site, and will meld back into it in time.

Stone

Of the 250 million tonnes of stone quarried annually in the UK, 90 per cent is crushed and used for aggregate. This dense and durable natural material is now being rediscovered by designers. Beautiful, less carbon intensive and typically stronger than brick and concrete, stone is infinitely reusable. It is available in a broad range of colours and textures, but it is heavy, however, so can be costly in fuel carbon to transport. Another consideration is that the thinner it is cut, for cladding for example, the more brittle it becomes, needing more support from other materials.

Limestone is formed from fossils of crustaceans on riverbeds. Its strength, texture and porosity will vary depending on the river water and the shells that form it. Limestone is less hard than granite, which comes from magma formed deep underground, or than marble, which is heated and compressed limestone. Limestone is easier to cut and shape but can be porous and so may stain or weather outdoors, or dissolve in acidic solutions, including polluted rain.

Sandstone is formed of sand compressed over long periods of time. Silica is a very hard material, so is difficult to shape and cut, and the strength will vary depending on how large the particles are and how well the silica is bonded. Yorkstone tends to be very hard, while some other sandstone will weather easily and undergo ‘freeze thaw’. This is when water gets inside the natural fissures and blows the layers apart when it expands in freezing conditions. The key to specifying stone is to ensure it is laid on a loose sub-base or with a lime mortar. If using a cement, ensure it is weaker than the stone so can be easily removed for dismantling, allowing infinite reuse.

Wood

This renewable resource sequesters carbon as it grows and holds on to it until it decomposes. It also stimulates an emotional biophilic response in humans. Being with trees is simply good for us. Being extremely versatile, wood fits well in a circular economy as it can be reused several times in different stages and forms, from main timber to smaller pieces or eventually to mulch or pulp. Sustainability is dependent on forestry management.

While UK-grown timber requires a felling licence with obligation to restock, 65 per cent of UK timber is imported each year, so certification and supplier traceability are key to sourcing. At the moment most harvested wood is destined for energy production, but applications in construction are growing, particularly with engineered wood. When choosing wood, ask where it is from and if it is certified, whether it has the right strength and durability for the purpose; discover whether excess moisture can be avoided through drainage or by raising it above soil level, and if any offcuts can be deployed on site or stored to sequester carbon.

The most durable woods for outside are oak (Quercus) and cedar (Cedrus), although Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) is a close contender and will be fit for many projects. Slow-growing tropical hardwoods are hard to justify as they take so much longer to replace and are often harvested to the detriment of their environment. The Tropical Forest Foundation, a non-profit organisation committed to environmental stewardship and sustainable forest management, recommends a reduced-impact logging method and offers demonstration models and training curricula in South America, Africa and South-East Asia. Always request certificates before buying wood.

Concrete

Concrete is financially economic, versatile, durable and resilient. It is easy to source, fire-resistant and heat-absorbent, so can be a good material to hold heat and cool areas. Because of the chemical reaction that binds the materials together when Portland cement is mixed with water, however, it also contributes 4–8 per cent of global emissions and is the single biggest building material greenhouse gas emitter.

There are emerging ways of reducing concrete’s carbon footprint: by using less Portland cement and substituting ground granulated blast-furnace slag (GGBS), itself in limited supply, or alternatives like limestone fill, calcinated clay and volcanic ash, which are gaining traction. To minimise impact, specify the right strength of concrete for construction, for correct longevity and also deconstruction. Recycle existing concrete on site, or upcycle elements elsewhere. Concrete is heavy on water use in manufacture and construction so substituting rainwater for mains water is also beneficial. As specifiers, designers and consumers, asking questions when choosing materials is often the first step to minimising our planetary footprint.

HOW TO CHOOSE BETWEEN BOUNDARY MATERIALS: A FENCE, WALL OR HEDGE

In many countries, residential garden fences are anathema, even banned by some US residents’ associations. In the UK we tend to have them, perhaps a remnant of our earlier moated ancestors.

When driving through the beautiful British countryside, it is a joy to see over hedges and through picket fences into gardens full of hollyhocks (Alcea rosea) and ox-eye daisies (Leucanthemum vulgare) in summer. It can be a shame when they are hidden behind tall, chemically treated, close-board, softwood fences. Fences like this can have a cheap initial cost and are often chosen to save horizontal space, but they are less good in other ways: too tall for neighbourly chats with a cup of tea, too opaque to see any lurking intruders, and too chemically treated to host wildlife

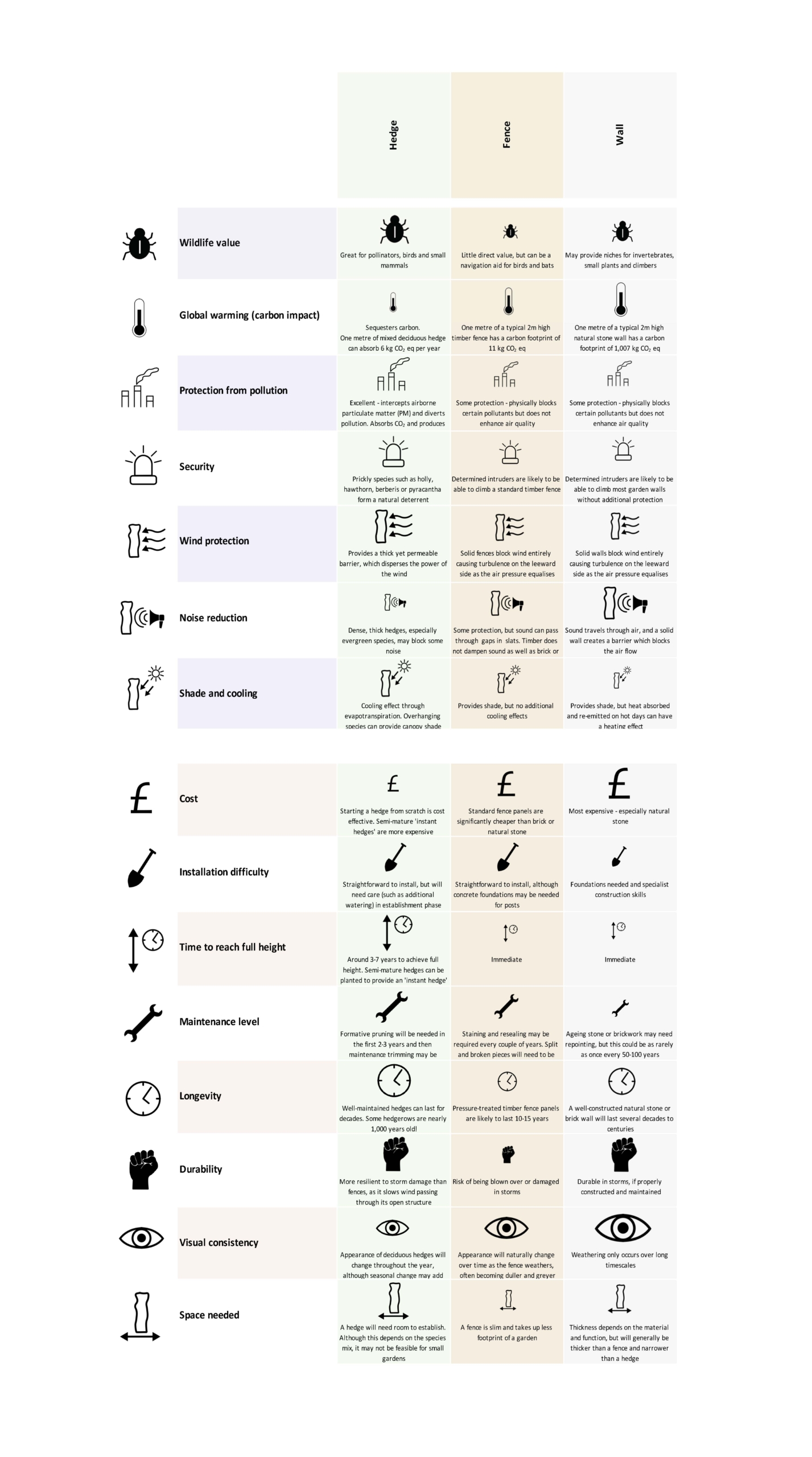

The table below compares some factors to consider in choosing between a hedge, a wall and a fence:

Photo © Jason Ingram. Diagrams © MBLA