The Kindest Garden – What is Regenerative Gardening?

When you let go of who you are,

you become who you might be.

Rumi

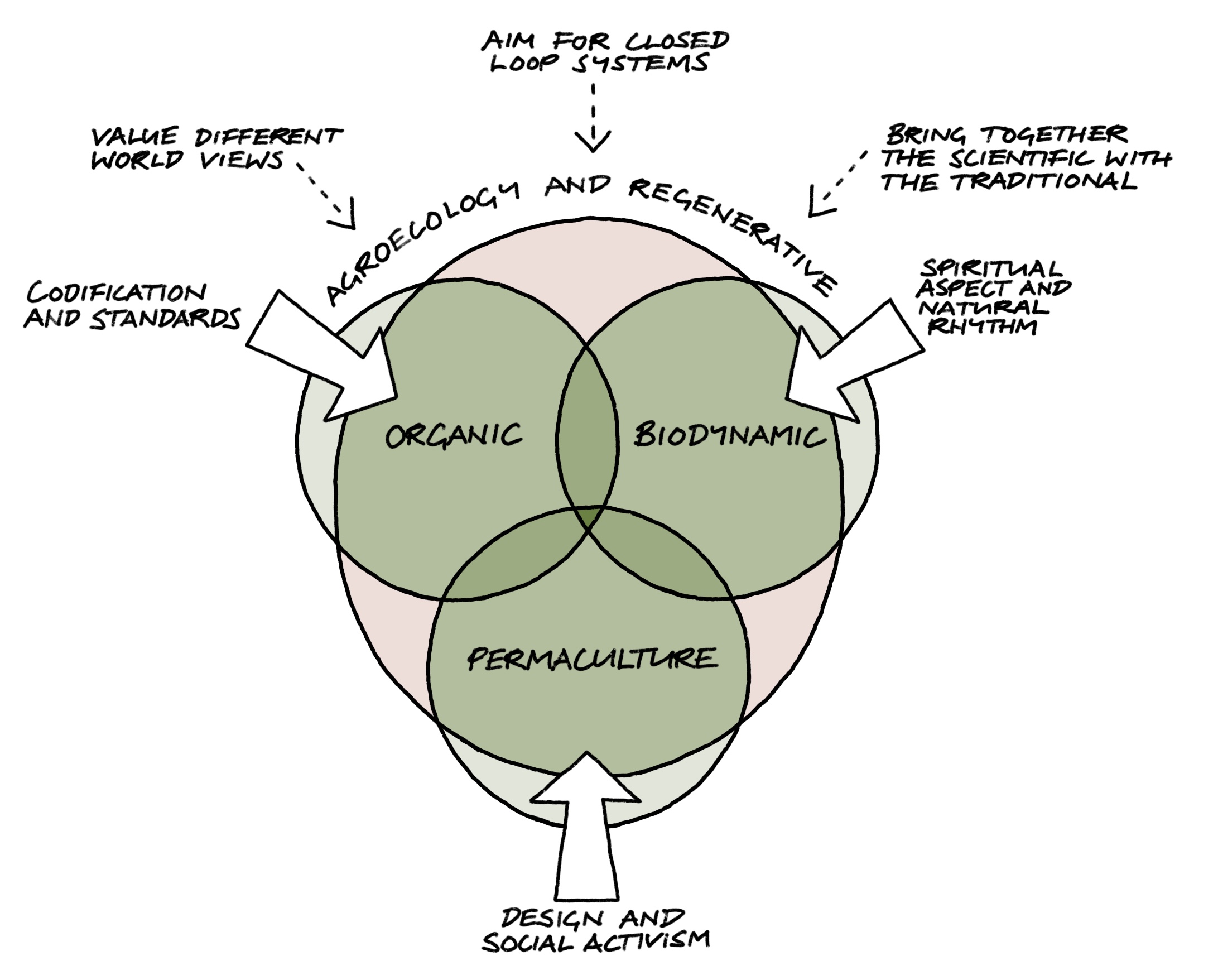

A regenerative garden isn’t just a place, or a method, to grow plants. It’s a mindset. It includes and goes beyond sustainability, focusing on making healthier land and people, and particularly healthier soil, which feeds all other ecosystems. Charles Massy in The Call of the Reed Warbler talks about the five landscape functions: the carbon cycle (solar energy); the soil system; the water cycle; biodiversity; and the human community ecosystem. Regenerative growers focus on all of these, and mix in learning from organic, biodynamic and permaculture approaches. It’s a movement in a high-energy, start-up phase that is gathering momentum and gravitas as it gains traction. This currently favours approach and intention over rules and certification, sharing resources, experimenting and pooling results according to context, without trying to roll out a one-size-fits-all solution.

Industrial growing

It’s easy to forget that industrial farming began with good intentions and pride in scientific discovery. There was a sense that nature could be leveraged without limit and without side effects, to sustain an ever-expanding urban population. Growing food at scale developed gradually from the sixteenth century in Europe and took off after 1909, when scientist Fritz Haber discovered a way to extract nitrogen from the air and fix it in solid soluble form as nitrates – a kind of salt applied to soil as fertiliser. Nitrogen is one of the three key macronutrients that fuel plant growth, along with potassium and phosphate, and is available in soil, organic matter and minerals, respectively. Before Haber’s discovery, extra nitrogen was traditionally added to the soil via animal manure (or human ‘night soil’), mined minerals and through growing legumes, which fix the nitrogen from the atmosphere in the soil through their roots and symbiotic bacteria. Nitrogen fertilisers were created to solve hunger and shortages after the two world wars, and they have delivered huge production to feed enormous populations ever since.

They have addressed many human problems, and the global payback took time to be understood. Over time we have discovered that the issues with the use of nitrate fertiliser are many. Nitrous oxide (a greenhouse gas) is produced when it is made, with fertilisers accounting for 6 per cent of greenhouse gas emissions. Nitrate is also a form of salt that kills many of the creatures in the soil that we call the soil microbiome. Once the microbes in the soil are killed, the plants no longer have access to the nutrients the microbes provide, and so like a drug addict they become ever more dependent on their chemical fix of nitrogen alone, and susceptible to diseases caused by the lack of others. Another issue is that nitrates are highly soluble and leech out of soil and into watercourses, where they can kill fish and cause eutrophication – the noxious green algal bloom responsible for blue baby syndrome. High nitrate levels are also a proven carcinogen in food.

As Marina O’Connell, founder of the biodynamic Apricot Centre asked: How might a more sustainable future look?

While Haber was inventing the nitrogen-fixing process, Paul Hermann Müller discovered that diffusion tensor tractography (DTT), which is derived from nerve gas, killed insects en-masse by interrupting their nervous systems. Together these discoveries enabled food production to become industrial in scale, but they degraded the soil, killing the insects and damaging mammals and the atmosphere in the process. The drive for yield and the introduction of tractors and new machinery also reduced numbers of mixed farms with livestock. Dairy cows were increasingly farmed in sheds, which created issues with their waste becoming mixed. This slurry was spread on the land as fertiliser and ended up polluting watercourses.

Other novelties compounded these problems. To grow plants at scale reliably, seed companies developed hybrid F1 seeds in the 1930s and 1940s. Because they are designed to be sterile and not need pollinators, they don’t reproduce naturally so they have created a dependency on seed companies, and disrupted natural pollination cycles. At the same time, paraquat (now banned) and glyphosate were created. Glyphosate kills plants from the roots up. Being a ‘systemic’ weedkiller, it stays in the plant’s system, and has been shown to enter the food system when the plant is eaten by cows, and go into our guts in their milk. It has taken time for us all to realise how these practices masse by interrupting their nervous systems. Together these discoveries enabled food production to become industrial in scale, but they degraded the soil, killing the insects and damaging mammals and the atmosphere in the process. The drive for yield and the introduction of tractors and new machinery also reduced numbers of mixed farms with livestock. Dairy cows were increasingly farmed in sheds, which created issues with their waste becoming mixed. This slurry was spread on the land as fertiliser and ended up polluting watercourses. Other novelties compounded these problems. To grow plants at scale reliably, seed companies developed hybrid F1 seeds in the 1930s and 1940s. Because they are designed to be sterile and not need pollinators, they don’t reproduce naturally so they have created a dependency on seed companies, and disrupted natural pollination cycles. At the same time, paraquat (now banned) and glyphosate were created. Glyphosate kills plants from the roots up.

Being a ‘systemic’ weedkiller, it stays in the plant’s system, and has been shown to enter the food system when the plant is eaten by cows, and go into our guts in their milk. It has taken time for us all to realise how these practices have been affecting our health and the health of our land. The steady reduction in birds, and the continued loss of insects since Rachel Carson wrote Silent Spring in 1962, have recently made it hard to ignore, and no one is quite sure where the shifting baseline was before that.

Hope through regenerative practices

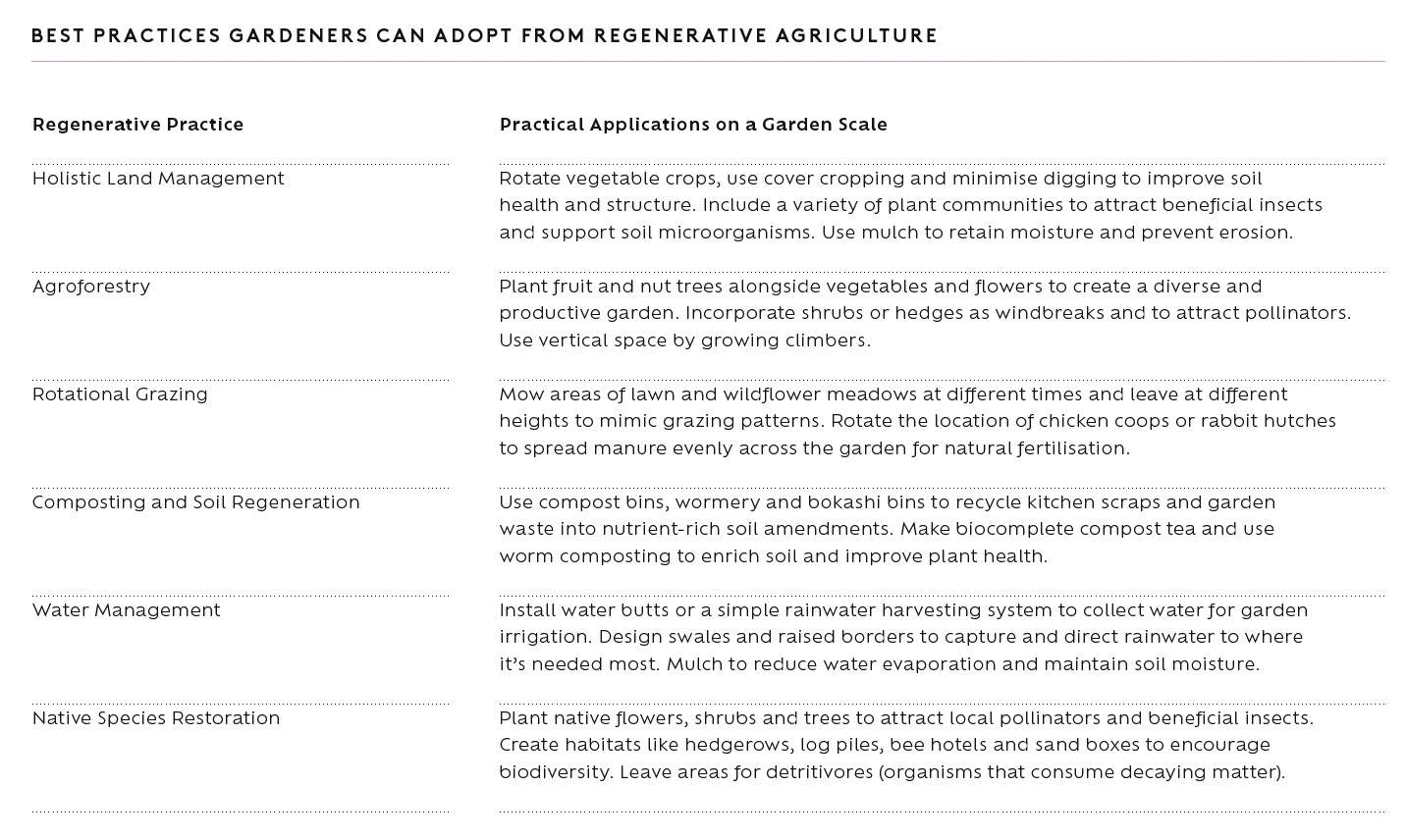

Amid the dominance of industrial agriculture, a parallel movement in smaller-scale agriculture has persisted, with farms below 2 hectares (5 acres) producing 30 per cent of the world’s food. Systems like organic, biodynamic, agroecological and permaculture growing were developed to challenge and resist industrial farming, offering well-documented practices and varying levels of training and certification all over the world. Regenerative growing is the synthesis of these approaches. Practised by gardeners, smallholders and at scale in different regions by pioneers like Allan Savory, John Kempf, Dr Elaine Ingham, Nicole Masters and the Wildfarmed movement, it aims to regenerate entire ecosystems. Its overarching principles include holistic ecosystem improvement, context-specific design, fair and reciprocal stakeholder relationships, and continual development of individuals, farms and communities.

Regenerative gardens

While each garden alone may seem small, it can play a pivotal role in this regenerative movement. The fact that there are some twenty-three million gardeners in the UK alone refutes any idea of gardens being irrelevant. Media, advertising and big business have allowed us to divorce growing food from the life cycle of the land, limiting the culture of the garden to a place of exclusively human pleasure that functions in two dimensions only – as an outside decorating opportunity. Regenerative gardening offers us a way to bring multidimensional life back into our gardens and realise that everything is food to someone, including ourselves. It is an approach that fosters biodiversity from the soil up, includes habitats throughout, increases carbon sequestration in our soils and trees, adapts to climate shifts and develops closed-loop systems. Key practices involve intentional design, mindful material usage, increasing biodiversity from soil to gut, harmonising with natural energies and conscientious plant sourcing. You don’t need a private garden to be part of the shift. Helping at a community garden or allotment can do huge good, as does joining a scheme like Sprout Club – an app linking people offering space to grow with people who want to grow. And those short of time can join a regular box scheme like Riverford, Farm Direct or Abel & Cole, or buy direct from growers and bakers, to eat seasonal healthy produce with fewer land miles and no chemical inputs.

Photo © Jason Ingram. Diagrams © MBLA