Setting the scene – the garden in the landscape

This article first appeared in Listed Heritage, the magazine for the Listed Property Owners’s Club.

In my first article on conserving a period garden I recommended beginning by researching the history and understanding the setting. This is key for a country garden as it will often have originally been planned to make the most of the setting, using the natural landform of the site when it was built.

Those canny local builders who knew their land so well may have sheltered you from north winds in the ley of a south facing slope, planted clumps of trees to break up the prevailing south westerlies on their way up a valley, framed the view and faced the key terraces to catch the morning and evening sun or the farmyard to make the most of natural springs and drainage. If that is the case you are lucky and it is vital to make the most of their local expertise in restoring the best of their design ideas.

They may also have positioned the house to sit on a once quiet lane to London or Edinburgh that has since become a busy road, or in such a cleverly strategic place that it has attracted many other houses in the intervening years, and that will be important to take into account in conservation measures too.

Old maps will show how the original layout may have changed with land ownership, the addition of buildings and extensions and planting fashions. In some of our clients’ gardens old views have been blocked by a plantation of then fashionable conifers, elegant long carriage drives have been sold off to neighbours and unfortunate buildings or extensions have turned a house around to face away from the best landscape setting. A metal army of electricity pylons might be marching across the best view or a hideous building might have gained planning permission in the middle of a key prospect. With a good design team, funds and correct permissions these are things which may be reversed, rectified or masked, and the long views and gracious setting can be returned.

My visit to a new garden or estate will always start with the setting: where the sun rises and sets, prevailing winds, the underlying geology and soils, natural flora and landform, and strategic views. The idea of Prospect and bringing the view in as a part of the landscape garden was popularised by William Kent who Walpole described as having “leapt the fence and saw that all nature was a garden”. Crucial to achieving this look is the judicious framing and opening up of key views, both on arrival and looking out from the house.

Trees are a wonderful way to frame a view and by choosing the species carefully they can form a formal frame or a softer transition to the countryside beyond. In the garden below I planted an allee of crabapples Malus hupehensis underplanted with Spirea arguta to be a gently mannered reflection of the rolling Wealden woodland and billowing hawthorn hedgerows beyond. The sculptural oak bench sits on a belvedere leading out to the oak woodland and demarcates the garden edge whilst framing the view beyond and referencing the local vernacular and traditional crafts.

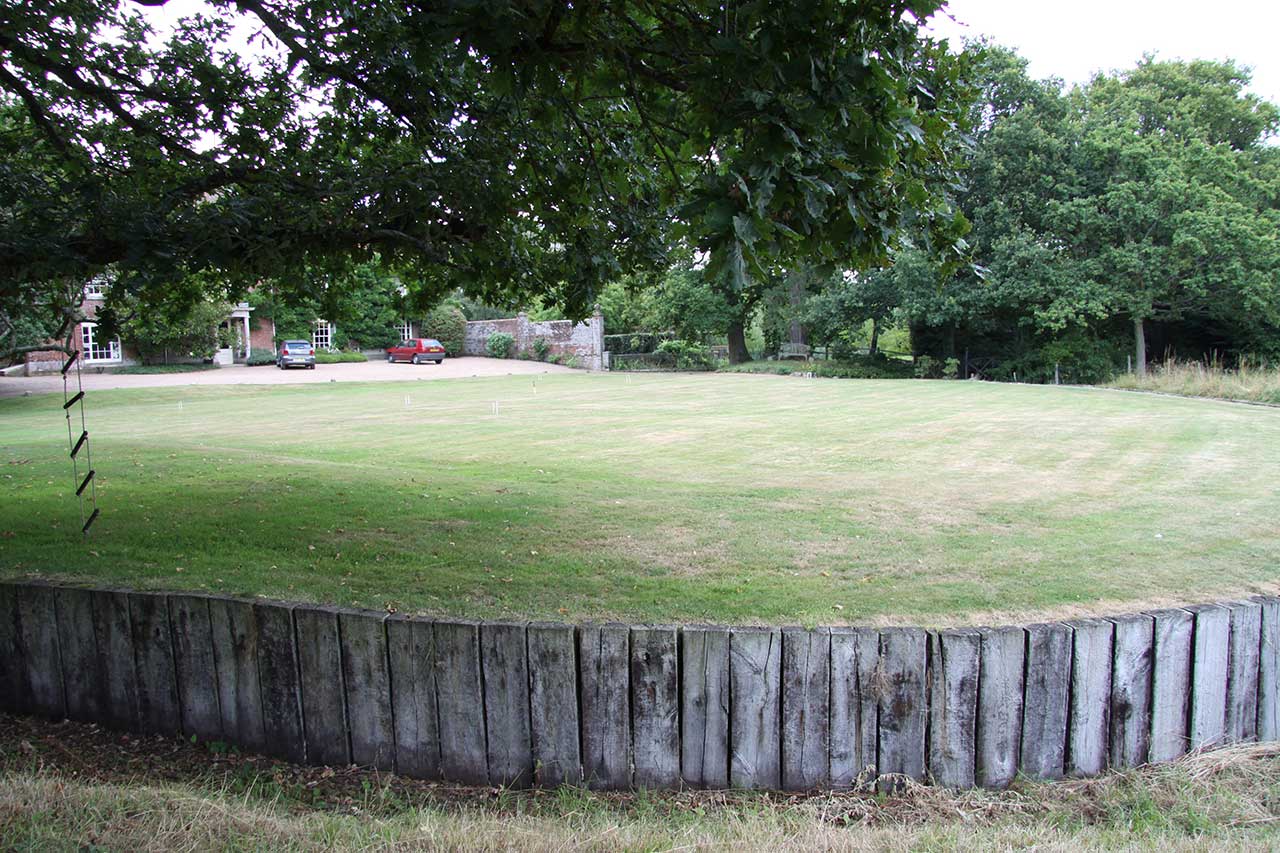

The clear boundary between garden and fields began to disappear in the 1700s with the sunken ditch or haha which became popular after being used by Beaumont at Levens Hall in 1690 and Charles Bridgeman at Stowe in 1740, where a 4 mile brick haha established this formal feature as a key transition from formal gardens to the landscape movement.

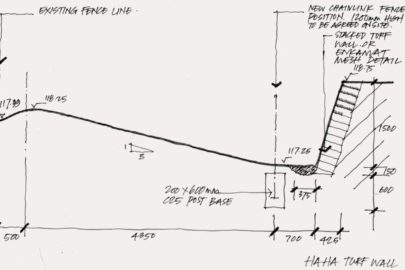

The traditional haha forms a barrier that cattle and sheep cannot cross on one side and that cannot be seen on the other (hence the exclamation of surprise or haha! When the land falls away). The haha is not seen from the house but may be seen from the landscape and so the finish should be taken into consideration. It will have a structural element and should be designed to retain the correct weight of soil above it, with more strength needed if there is a house or pool above for example and with footings which will depend on the load bearing ability of the soil (measured as the CBR or California Load Baring Ratio).

The soil conditions will dictate the construction. A traditional haha may have been built as a dry stone wall for example if the conditions are right. A cost effective way of building a new haha is to use reinforced masonry construction such as hollow concrete blocks with concrete infill and reinforcing bars down the centre.

The concrete foundation was laid to engineers’ details (see image above) to cope with the height of wall and the hollow blocks were then reinforced and grout filled. Behind the wall vertical drainage membrane and perforated land drain are placed to cope with hydrostatic pressure and drainage off the land above. This is connected into the land drainage system and water is taken off site via a shallow swale planted for wildlife.

The wall can be clad in a range of finishes such as stone, brick, corten steel, render or timber. The finish on top of the wall will depend on the type of cladding and how visible you want it to be. In this case we used a simple vertical steel edge and continued the wild flower meadow right up to the edge to provide a seamless transition.

In another setting a low haha is clad in reclaimed brick and reclaimed york stone defines the top with a subtle horizontal line leading out to the valley beyond.

The image above shows the wall before the mound and ditch were formed on the field side to hide the haha from the view, whilst the image below shows it blurring the boundary from the garden side.

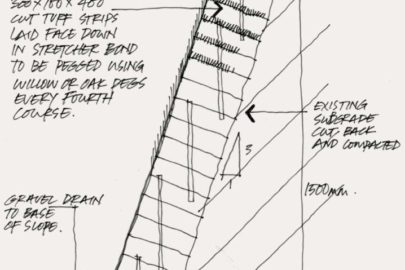

Another soft effect where the haha might be prominent in the landscape is to use a reinforced grass or turf wall. This is similar to the traditional Devon bank which was made of clods of turf built up in a batter and can look lovely.

An existing haha may be listed either in its own right or as part of the curtilage of the listed property and so a conservation officer should be consulted before restoration work is undertaken. Other considerations are any nearby tree roots which should be carefully avoided. Hand digging will always be necessary inside a root protection zone, and excavation work in sensitive settings might need the involvement of an archaeologist.