Bringing Paradise To Your Garden

Since ancient times gardens have offered protection, nourishment and delight. Marian suggests how to turn your outside space into a personal paradise.

Personal paradise

When you think back to your happiest memories outdoors, what were you doing? What could you hear and what could you smell? Who were you with? Getting to know a new garden design client is a bit like speed dating – I need to understand quickly and in some depth what their personal paradise feels like.

It’s not what people have that makes them happy, but an emotion or memory they associate with what they have. You can pay a fortune for a certain garden, but if it does not feed your own personal paradise, it will not bring you fulfilment.

Since the Persian ruler Cyrus the Great created his palace gardens in the 6th century BCE, we have strived for protection, nourishment and delight. Protection came through walls, with the word paradise coming from the Persian para deiza, or enclosed garden. Nourishment and shade came from orchards of nuts and fruit, and delight came from the layout, colours, scents and flowers of the trees, enhanced by planting them alongside raised walkways. As well as providing a physical oasis in the harsh desert environment, these early gardens were designed to engender spiritual succour. Sacred geometry was used to divide the space into a chahar bagh (four gardens), with water channels representing the four rivers of life, bringing coolness, light and sound energy from sources deep in the mountains. This quadripartite layout was adopted by the Muslim Arabs after the 7th-century conquest of Persia and established the pattern of the celestial garden of the Quran.

First steps to heaven

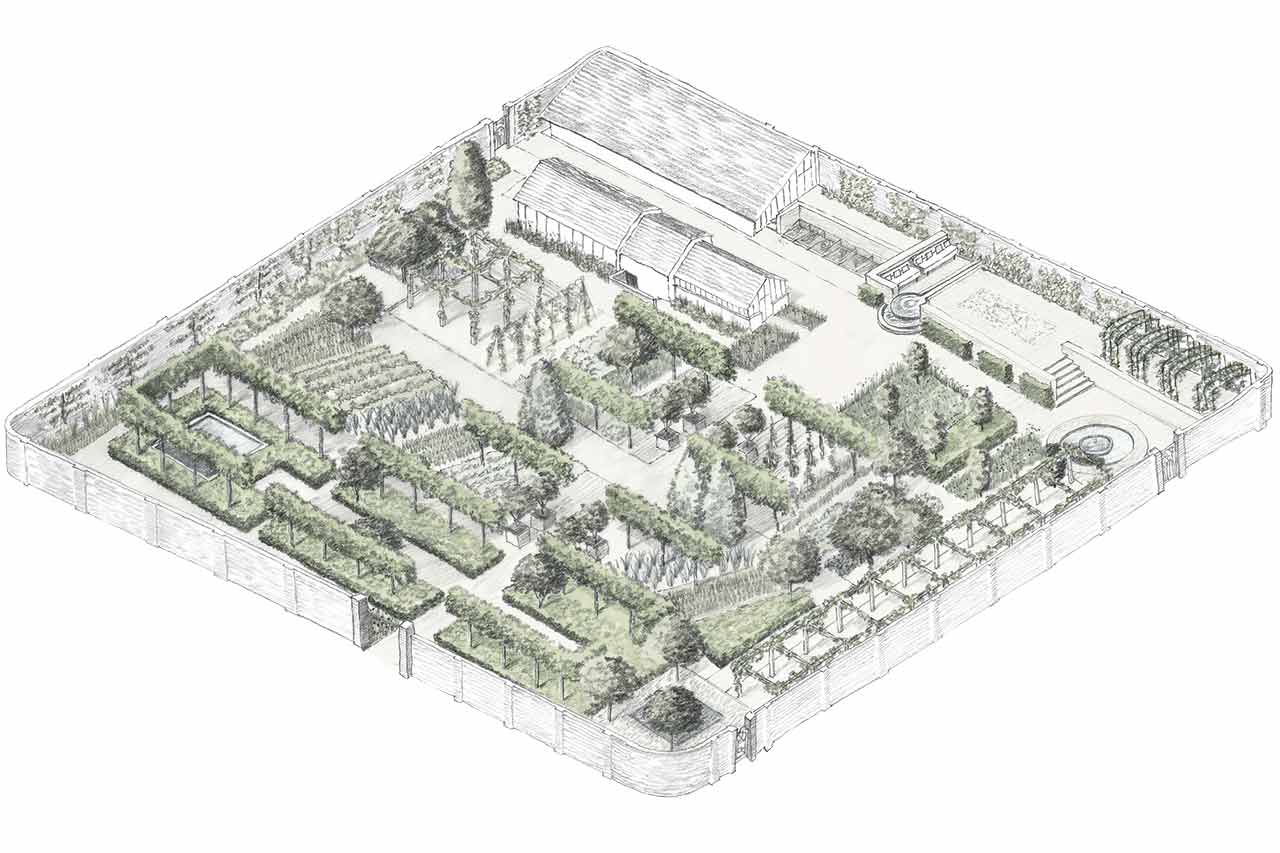

In Christian philosophy, the Garden of Eden represents the Platonic ideal of a perfectly happy state. Landscapes, such as Stowe, the William Kent-designed garden in Buckinghamshire, evoked heaven on earth with a bucolic English version of the Elysian fields. As layouts evolved in the English landscape style, the walled garden moved away from the main house where it often continued the geometry and fecundity of a paradise garden alone in its seclusion as a vegetable potager. In these days of instant gratification, do you know what makes you truly happy? If so, how can you use that to create your own paradisal garden? First, ask yourself what is this garden for? Is it a space for celebration, exhilaration or healing, for example? How is it going to serve your vision of a perfect world?

Many people look for refuge in their gardens, and it’s important to make enclosure an aesthetic part of the design, especially in small gardens where every feature needs to contribute. Walls work well for training fruit and keeping out marauders, but it is cheaper – and better for wildlife – to plant a hedge, or clothe a fence with climbers. An edible hedge gives nourishment, and, if there’s room, fruiting trees can add to the table, support pollinators and provide shade.

Water is a sacred element, even in rainy UK. Fountains make light and sound dance, and a reflection pool brings sky to earth and creates a theatre of skimming dragonflies, bats and birds. A raised walkway recalls the stepped poetry platforms of the Shalimar Gardens in Lahore, and arbours with a succession of climbers bring flowers and fruit to eye level. The layout uses the geometry evolved through millennia, but glasshouses have replaced pavilions, and materials and planting are adapted to suit the British topography and weather.

Like garden, like owner

The Persian garden ideals were adapted and carried along the Silk Road to India in the early 16th century and one of the best-known paradise gardens still in existence is at the Taj Mahal. A garden celebrating love, the shapes and materials were chosen to symbolise the divine feminine by reflecting the light at dawn and sunset to embody different moods.

Our choice of materials reflects our personal mindset, and in my designs reclaimed local materials maintain a link to the land – past and future. The Taj Mahal paradise of soft fruitfulness speaks of fecundity and its original planting of roses and jasmine, scented herbs and fruits are often easier to grow in a western climate. In a classical Paradise garden, everything is perfect, geometrically and symmetrically: proportions, spacing and colours are in perfect harmony and revere the divine. Although this works well in a contained space or in contrast to the barren desert, earthly paradise in the English countryside may feel more comfortable if worn a little looser. The Paradise-style Carpet Garden at Highgrove, for example, is more at ease now than when it was new, as years of gentle wear and self-seeding have softened its lines.

However small the space, we can create vignettes of our personal paradise: in the way a wild rose frames a view, a rustic bird bath splashes beneath a window, a seat curves beneath a plum tree, or thyme creeps between paving stones. These snatches of memory don’t have to be large, or to cost the earth, and they will mean different things to each of us. Every time we try something new, we learn a little more about what works and what brings us fulfilment. We think we are shaping a garden, when actually it is shaping us.

This article first appeared in Gardens Illustrated Magazine, September 2019