Creating a Garden To Endure

A design that will stand the test of time is key to a flourishing ecosystem and a more sustainable garden.

Why do some gardens last for hundreds of years and become a treasured part of the landscape, while others are soon ripped out and redesigned? Town and city gardens especially seem to fall foul of changes in fashion, but stability is vital to creating a flourishing ecosystem as well as reducing our waste and impact. So how can we ensure that the gardens we inherit or create will stand the test of time?

Sustainability was not a buzz word in Ancient Rome when the architect Vitruvius wrote his seminal design manual De Architectura (On Architecture). His ideas have deeply influenced British design, largely through the work of the Scottish architect Colen Campbell, who published his own great work Vitruvius Britannicus in three volumes between 1715 and 1725. These principles are still universally relevant today when designing buildings and gardens to endure. Vitruvius had advocated three tenets: firmitas, utilitas and venustas, which translate as strength, utility and beauty, ideas that reach across the centuries to the famous dictate of the 19th-century polymath William Morris that you should ‘have nothing in your house that you do not know to be useful, or believe to be beautiful’. Even today when we look to design our own gardens all of these tenets hold true.

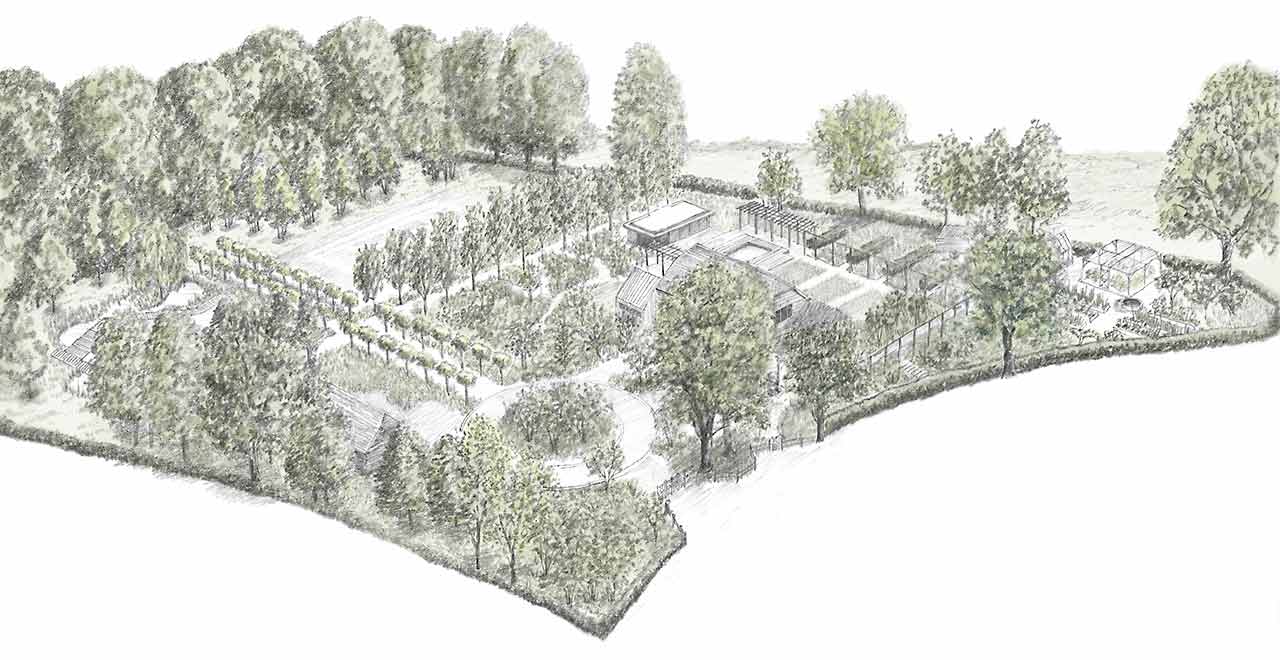

To be durable and robust a garden must fit with the land, be of the land and eventually be able to return to the land. This means a design that works with the site aesthetically and practically, and using well-crafted, carefully chosen materials and solid construction methods. By observing the land we can see where the wind comes from, where shade is cast and privacy needed and so where trees, hedges and long-term structures will be best sited. On land with a sandstone geology and a clay soil, for example, it makes sense to use sandstone pavers and clay brick so that one day when we are long gone the materials can meld back into the land. We can also watch where water runs and where it pools, to see where drainage is needed and where we can collect water to reuse. By planting trees and using wood to construct paths and structures we can lock up carbon. By using local natural materials, which are often reclaimed and can be reused whenever possible, we avoid waste and ensure we are following the principle of do no harm to the land long term.

To be useful, a garden must work practically, so access and circulation should make sense, pathways should go where there is a desire line to walk frequently and to keep feet dry in wet weather – and shelter, seats and low-impact utilities should be sourced and placed just where they are needed. By choosing plants that flourish in the conditions and that fix nitrogen or provide food and forage or deter the uninvited, nothing is wasted. By planting densely and in harmonious layers we again lock up carbon, reduce pests and disease and create a self-supporting ecosystem to endure. Adding organic matter and avoiding artificial fertilisers and pesticides will make sure the soil is healthy and that it contains all the beneficial bacteria and fungi plants need to get their nutrients from the soil – a bit like giving it a healthy gut.

Earthly delights

When a garden is delightful you can sense the love and thought that has gone into it. From the scents that greet you to the colours and textures and placing of things ‘just so’, this is what makes us fall in love with a place, buy a house and want to continue to nurture a garden. Harmonious planting and use of light are key to this esoteric essence of a place. Since before Hadrian built his villa in Tivoli, using Vitruvius’s principles, in the second century AD, we have aligned our buildings and gardens to the path of the sun, and the once glimpsed magic of a backlit border or bank of roses at sunrise is reminder enough to place key plants where they will get the spotlight.

When deciding what style to make a garden it is wise to look to the style of house we have chosen but also our own inner sense of paradise, which will fulfil us beyond any fleeting trend. Contemporary or traditional in taste, timeless elegance never goes out of fashion, and if we visit the gardens of Repton, Harold Peto’s Iford, or Norah Lindsay’s Blickling Hall, for example, we can see how good design intention stands the test of time. And finally we can celebrate ageing without throwing things away. The Japanese celebrate imperfection and transience in the philosophy of wabi-sabi whereby form evolves, natural materials take on the gradual patina of age, and old trees are venerated for their mature shape and beauty.

A garden is a labour of love that embodies so much about how we care for ourselves and the planet. Our aim in creating a garden to endure is to ensure reciprocity: for the garden to be delightful, useful and do no harm, so that when we leave the land we will have put back more than we have taken out.

This article first appeared in Gardens Illustrated Magazine, December 2019

Categories